Combining Data: Attributes

Contents

Combining Data: Attributes¶

Combining different measurements over the same individuals¶

Adding additional attributes to an existing dataset is often necessary to improve the description of the data generating process and answer the questions being asked of the data. In its most simple form, such a task consists of tables of the same individuals, with different attributes, collected for different purposes.

Such a process simply needs to add the columns of the second table to the first table. However, this process only works when the rows of the two tables correspond to the same individuals. Assuming a one-to-one correspondence between the individuals in the two tables, identified by their index, combining the columns of the two tables requires two steps:

sorting each table by their respective indexes (i.e. lining them up),

iterating through the (common) index of each table, combining the attributes of each row into a new table.

Remark 1: This procedure is implicitly done by Pandas whenever setting a Series as a new column of an existing DataFrame.

Remark 2: Understanding the internals of this procedure is important for both being able to debug performance issues, as well as implement custom procedures when the correspondence between the rows of the tables is not obvious.

This procedure is known as joining or merging tables (column-wise). The correspondence between the rows (e.g. via a shared index) is called a join key.

Example: Below, two tables contain characteristics of California counties obtained from the US Census: one contains a population attribute, the other contains the median household income. The join key is the ‘County’ column.

Joining data column-wise¶

Pandas has multiple ways of executing a (column-wise) join of DataFrames. Below outlines each and their relative advantages. In spite of the options, one should use the merge method whenever possible!

Join Technique 1: column(s) assignment The most simple way of joining the columns of two tables along a shared index is by column(s) assignment. If df1 and df2 have indexes in one-to-one correspondence, they can be joined via:

df1[df2.columns] = df2

This technique is simple and space efficient, since column assignment modifies the left-hand DataFrame in-place. However it has many disadvantages:

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|---|---|

Space Efficient |

Doesn’t work with the method chaining |

— |

Joining more than two DataFrames requires multiple lines |

— |

Works only when indexes are in one-to-one correspondence |

— |

Sorts the two DataFrames by index, even if already aligned |

Join Technique 2 (concat): The Pandas function concat column-wise joins a list of DataFrames by a shared index, with several convenient keyword arguments. If df1,...,dfN are DataFrames, then the columns of these DataFrames can be joined by passing them to concat in a list:

pd.concat([df1, ..., dfN], axis=1)

This function has many advantages over column assignment:

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|---|---|

Can easily join many DataFrames |

Doesn’t work with method chaining |

Indexes don’t need to be 1-1 correspondence |

The DataFrames must of a common index |

Can skip sorting indexes by setting |

Join Technique 3 (merge): The merge method is the most flexible joining technique in Pandas. By default, it joins the columns of two DataFrames on common columns. If df1,...,dfN are DataFrames with shared columns that identify observations between them, the DataFrames can be joined by chaining together successive merge calls:

df1.merge(df2).merge(df3)...merge(dfN)

If the DataFrames have a shared index, then merge is called with the left_index/right_index=True keyword argument.

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|---|---|

Works with method chaining |

Can’t pass an arbitrary list of DataFrames |

Join key doesn’t need to be in index |

Can’t skip sorting by the join key |

Rows don’t need to be 1-1 correspondence |

Example:

counties = pop_counties.merge(inc_counties)

counties

| County | Population | Income | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Calaveras | 44921 | 54936 |

| 1 | San Diego | 3183143 | 63996 |

| 2 | San Joaquin | 701050 | 53253 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 55 | Marin | 256802 | 91529 |

| 56 | Monterey | 424927 | 58582 |

| 57 | San Mateo | 739837 | 91421 |

58 rows × 3 columns

Check the relative sizes of the inputs confirm every row has its expected match. The input tables exactly one entry for each of the 58 California counties; the joined table should have one row per county and three columns.

print(pop_counties.shape, inc_counties.shape, counties.shape, sep='\n')

(58, 2)

(58, 2)

(58, 3)

Remark: this simple check can save hours of debugging!

Join types¶

Not uncommonly, when joining two tables, the observations don’t perfectly align. In these cases, care must be taken with the approach to joining the observations. There are three possibilities:

the observations are in one-to-one correspondence,

one of the tables contains observations not contained in the other,

both of the tables contain observations missing in the other.

In the first case, there is no ambiguity in combining the two tables. However, in the latter two cases, one has to decide whether to retain the observations that are present in only one of the tables. These cases are enumerated in the following join types.

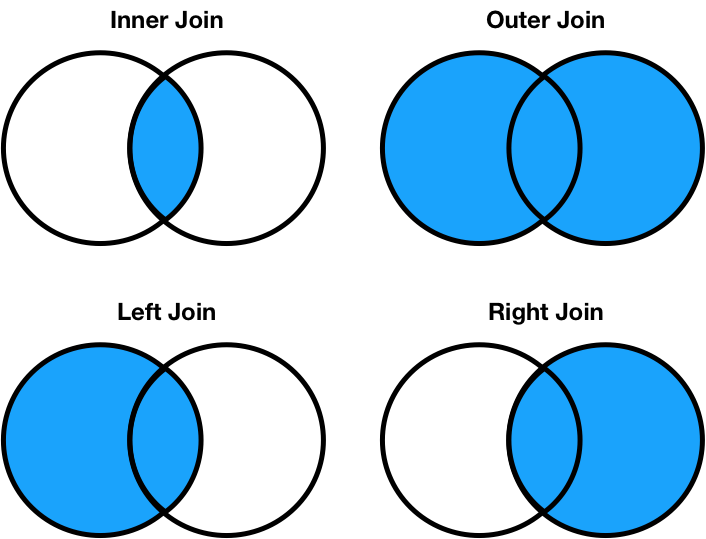

Given two tables, the possible join types of a combined table are:

An inner join keeps only the observations with a matched join key,

An outer join keeps all observations, even if not-matched,

A left join keeps all observations in the left table,

A right join keeps all observations in the right table.

Below, the join types are illustrated with Venn diagrams; the diagrams overlap if the tables share an observation:

The default operation is typical as inner join, as is true for the merge method.

Example: Suppose the county population table only includes information on counties with populations over 1.5M residents. The inner-join between this partial population table and the full income table will drop income information!

The partial population file only contains seven of the 58 counties:

partial_pop = pop_counties.loc[pop_counties['Population'] > 1.5*10**6]

partial_pop

| County | Population | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | San Diego | 3183143 |

| 9 | Riverside | 2266899 |

| 18 | Santa Clara | 1841569 |

| 24 | San Bernardino | 2078586 |

| 37 | Los Angeles | 9974203 |

| 50 | Alameda | 1559308 |

| 53 | Orange | 3086331 |

The inner-join only contains the seven large population counties, even though the income table contains all 58 counties:

partial_pop.merge(inc_counties)

| County | Population | Income | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | San Diego | 3183143 | 63996 |

| 1 | Riverside | 2266899 | 56592 |

| 2 | Santa Clara | 1841569 | 93854 |

| 3 | San Bernardino | 2078586 | 54100 |

| 4 | Los Angeles | 9974203 | 55870 |

| 5 | Alameda | 1559308 | 73775 |

| 6 | Orange | 3086331 | 75998 |

A right-join retains all the income values and adds population entries when available; a NaN value appears when a corresponding county doesn’t appear in the population table:

partial_pop.merge(inc_counties, how='right')

| County | Population | Income | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | San Diego | 3183143.0 | 63996 |

| 1 | Riverside | 2266899.0 | 56592 |

| 2 | Santa Clara | 1841569.0 | 93854 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 55 | San Benito | NaN | 67874 |

| 56 | Yolo | NaN | 55508 |

| 57 | Lassen | NaN | 53351 |

58 rows × 3 columns

Example: Joins in Pandas are exact matches between join keys, including a match on the data type. For example, columns with integer columns, with one of them typed as a string, will fail to properly join. These mistakes are hard to spot, as Pandas hides the type of the contents of DataFrames on formating.

Defining two dataframes with matching indexes of different types:

df_ints = pd.DataFrame({'B': range(0, 6, 2)}, index=[0, 1, 2])

df_strs = pd.DataFrame({'C': range(0, 12, 4)}, index='0 1 2'.split())

Joining the two DataFrames with an outer-join illustrates the failure to join on index:

merged = df_ints.merge(df_strs, right_index=True, left_index=True, how='outer')

merged

| B | C | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.0 | NaN |

| 1 | 2.0 | NaN |

| 2 | 4.0 | NaN |

| 0 | NaN | 0.0 |

| 1 | NaN | 4.0 |

| 2 | NaN | 8.0 |

The index of the merged table contains distinct values of both integer and string type:

merged.index

Index([0, 1, 2, '0', '1', '2'], dtype='object')

Example: By default, merge sets the join-key to the set of all common columns between the DataFrames being merged, sometimes leading to unintended consequences when both tables share similar attributes. The join-key can be specified explicitly using the keyword on.

The DataFrames df1 and df2 have different resulting joins when the join key is column ‘A’ vs. columns (‘A’, ‘B’):

df1 = pd.DataFrame({'A': range(3), 'B': range(0, 6, 2)})

df2 = pd.DataFrame({'A': range(3), 'B': range(0, 12, 4)})

df1.merge(df2)

| A | B | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

df1.merge(df2, on='A', suffixes=['_1','_2'])

| A | B_1 | B_2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

Remark: The suffixes argument decorates the duplicate column names with which table the column originated from.

Example: When joining new attributes to a dataset under investigation, the additional information isn’t always available for the complete population. For example, when investigating the incomes by California county, suppose one attempts to join demographic information (such as population size) to the incomes dataset. However, if this demographic information is only available for counties with a large population, the merge dataset will exhibit significant bias:

large_pop = pop_counties.loc[pop_counties['Population'] > 200000]

Upon merging the incomes with the demographics, an inner-join drops all counties of small size. The resulting average income is quite different than the average income across all counties:

inc_counties.merge(large_pop)['Income'].mean()

63668.57142857143

inc_counties['Income'].mean()

56034.362068965514

By using an left-join, on can avoid dropping these observations (at the expense of introducing missing values into the merged dataset):

inc_counties.merge(large_pop, how='left')['Income'].mean()

56034.362068965514

Many-to-one joins¶

A join performed on a join-key with duplicate entries results in either a ‘many-to-one’ or a ‘many-to-many’ join. Though these joins occur naturally, the resulting datasets might initially seem unintuitive.

Many-to-one joins occur naturally when using ‘lookup tables’ to attach richer information about an attribute of a dataset (as opposed to an individual). For example, a table might include the purchase history of customers subscribing to a music-streaming service:

Customer |

Plan Type |

|---|---|

23523 |

Premium |

43453 |

Premium |

34523 |

Student |

… |

… |

98345 |

Family |

13423 |

Premium |

34234 |

Student |

Computing the total revenue generated from these purchases, one needs to merge this table with the three-row table of plan types:

Plan Type |

Price |

|---|---|

Student |

$4.99 |

Premium |

$9.99 |

Family |

$14.99 |

A few observations on how this join differs from the simple joins covered before:

the join-key ‘Plan Type’ is an attribute of the table, not an identifier for the observations of the tables.

one expects the resulting joined table to contain the price next to each customer purchase; the each row in the small table is repeated many times over.

The result of joining these two tables is:

Customer |

Plan Type |

Price |

|---|---|---|

23523 |

Premium |

$9.99 |

43453 |

Premium |

$9.99 |

34523 |

Student |

$4.99 |

… |

… |

… |

98345 |

Family |

$14.99 |

13423 |

Premium |

$9.99 |

34234 |

Student |

$4.99 |

Example: The dataset cities contains population and income information on 1442 California cities, along with the name of the county to which each city belongs. Using this dataset, one can roughly calculate which cities make significantly more or less than their neighbors: create a derived attribute using the ratio of the average household income of a given city to the average household income of the county in which it lies.

cities

| City | County | Population | Income | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Acalanes Ridge | Contra Costa | 1226 | 160000.0 |

| 1 | Acampo | San Joaquin | 776 | 141250.0 |

| 2 | Acton | Los Angeles | 6956 | 92245.0 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1439 | Yucaipa | San Bernardino | 52406 | 58506.0 |

| 1440 | Yucca Valley | San Bernardino | 21083 | 43086.0 |

| 1441 | Zayante | Santa Cruz | 853 | 81308.0 |

1442 rows × 4 columns

Calculating this attribute requires joining the county dataset with the city dataset on the ‘County’ attribute. Since possibly many cities belong to the same county, this is a many-to-one join.

cities_with_county_info = cities.merge(counties, on='County', suffixes=['_city', '_county'])

cities_with_county_info

| City | County | Population_city | Income_city | Population_county | Income_county | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Acalanes Ridge | Contra Costa | 1226 | 160000.0 | 1081232 | 79799 |

| 1 | Alamo | Contra Costa | 15639 | 163151.0 | 1081232 | 79799 |

| 2 | Alhambra Valley | Contra Costa | 499 | 62000.0 | 1081232 | 79799 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1435 | San Juan Bautista | San Benito | 2219 | 57717.0 | 56888 | 67874 |

| 1436 | Tres Pinos | San Benito | 457 | 75893.0 | 56888 | 67874 |

| 1437 | San Francisco | San Francisco | 829072 | 78378.0 | 829072 | 78378 |

1438 rows × 6 columns

Remark: What happens if the join key were not specified in the merge? What condition must be met for a city to belong to the merged table?

Once merged, the ‘income ratio’ attribute is simply the ratio of two columns. The cities with the highest income ratios are small gated communities within Los Angeles County:

(

cities_with_county_info.assign(

income_ratio=cities_with_county_info['Income_city'] / cities_with_county_info['Income_county']

).sort_values(by='income_ratio', ascending=False)

)

| City | County | Population_city | Income_city | Population_county | Income_county | income_ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 134 | Hidden Hills | Los Angeles | 1749 | 245694.0 | 9974203 | 55870 | 4.397602 |

| 177 | Rolling Hills | Los Angeles | 1689 | 218583.0 | 9974203 | 55870 | 3.912350 |

| 169 | Palos Verdes Estates | Los Angeles | 13568 | 171328.0 | 9974203 | 55870 | 3.066547 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 595 | Boulevard | San Diego | 434 | 12421.0 | 3183143 | 63996 | 0.194090 |

| 1301 | Valley Ford | Sonoma | 167 | 9312.0 | 491790 | 63799 | 0.145958 |

| 526 | Verdi | Sierra | 92 | 4853.0 | 3019 | 43107 | 0.112580 |

1438 rows × 7 columns

Many-to-many joins¶

Recall that, assuming a one-to-one correspondence between the individuals in the two tables, joining the columns of the two tables requires two steps:

sorting each table by their respective join-keys (i.e. lining them up),

iterating through the (common, corresponding) rows of each table, combining the attributes of each row into a new table.

Now, consider if one, or both, of the tables contains duplicate values in the column specified as the join-key. How does step 2 change? Sketch out an algorithm. How many rows does the resulting joined table have?

Broadcast join¶

When one of the tables being joined is small, it’s faster to use a broadcast join. Broadcast joins use the following procedure:

load the small table into a dictionary \(D\), keyed by the join-key.

iterate through the large table; for each row \(r\) in the table:

access the join key \(k\) for that row,

get the value \(v = D[k]\) corresponding to this key,

append the value \(v\) from the dictionary to the row \(r\).

This procedure is fast:

it doesn’t require sorting either table,

dictionary lookups only require constant time,

So this sorting algorithm runs in a time proportional to the sum of the lengths of the two tables.

Example: Given the two tables of streaming music purchases (purchases), and the prices of each plan type (prices), one can use a broadcast join to combine the two tables on ‘Plan Type’:

D = prices.set_index('Plan Type').to_dict()

purchases['Price'] = purchases.apply(lambda x:D.get(x['Plan Type']))